The previous post in this series discussed Mary Anthony’s career as a woman’s rights-minded educator. But it is as a suffragist and partner of her famous sister Susan, rather than her feminist forays in the field of education, for which Mary Anthony is best remembered.

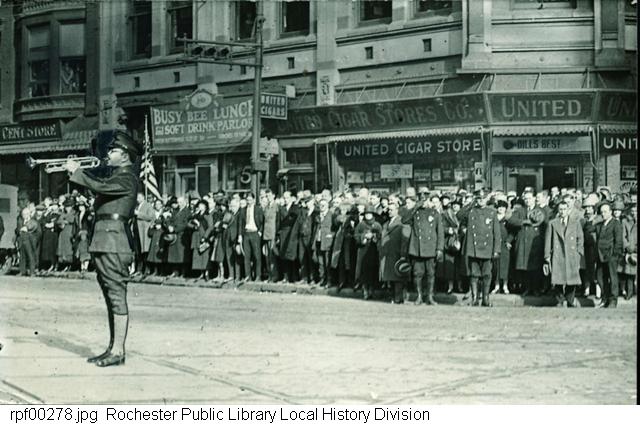

Susan B. Anthony (L) and Mary Anthony (R). From: The Collection of the Rochester Public Library’s Local History & Genealogy Division.

Susan B. Anthony testified to her sister’s devotion to the suffrage cause in an 1897 interview with the Union and Advertiser: “She attended the first equal rights convention ever held in Rochester. When I came home from school, I found Mary full of it. I found nothing but equal suffrage talk … I didn’t believe in it then and made fun of it.”

When Susan joined the woman’s rights movement, the two became partners. While Mary rarely spoke in public, she looked after the “great mass of details” connected with the suffrage movement, allowing Susan to travel frequently. “Without her,” Susan claimed in the aforementioned interview, “I never could have done what I have for the women of America. She is the unseen worker who shares equally in whatever reward and glory I may have won.”

The Anthony sisters’ home at 17 Madison Street. From: City Hall Photo Lab.

Mary displayed her impressive organizational skills during the New York State Constitutional Convention (May 8, 1894–September 29, 1894). The convention was charged with proposing a new constitution for the state, and Mary and Susan were determined to have a woman’s suffrage provision included.

Mary was responsible for distributing petitions that resulted in 500,000 signatures in support of equal suffrage. She also directed the distribution of campaign literature on the subject. Unfortunately, the effort fell short. New York State did not give women the vote until 1917.

Unlike her sister, Mary was not known as a public speaker, but she could make her views known when roused. In 1896, the Rev. Algernon Crapsey, rector of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, preached a sermon at which Mary took umbrage.

Dr. Algernon Sidney Crapsey (1847–1927),

Rector of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, Rochester. From: The Albert R. Stone Negative Collection, Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, N.Y.

In his address, Crapsey detailed the “evil results” arising from women and girls selling the woman’s edition of the Rochester Post-Express newspaper on public streets and streetcars.

According to Crapsey, it was “contrary to good manners and good morals for women to approach men on the streets, or in other public places, for any purpose whatsoever.” He further alluded to them as “mannish women.” Mary replied to him as follows:

Is it not an insult to the hundreds and thousands of women who are today earning an honest livelihood – oftentimes supporting aged parents or young brothers and sisters or both? If members of his own family were thus forced, through adverse circumstances, to earn their daily bread, would he not wince to hear them spoken of as unwomanly and unrefined?

Mary did not long survive her more famous sister. After Susan’s death in March 1906, she filled in for the suffragist at previously scheduled rallies and meetings. Upon returning from a speaking tour in Oregon eleven months later, she suddenly fell ill and passed away on February 5, 1907. She was two months shy of her 80th birthday. She lies buried next to Susan in Mount Hope Cemetery.

Mary S. Anthony’s grave in Mount Hope Cemetery. From: Emily Morry, 2020.

– Christopher Brennan

For Further Information:

Finn, Michelle. “The Other Anthony Girl,” LocalHistoryRocs! (March 25, 2013). Available here:

https://rochistory.wordpress.com/2013/03/25/the-other-anthony-girl/

Harper, Ida Husted. Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony (1898-1908; reprint, New York, Arno Press, 1969).

“Anthony Reception: Rochesterians Will Celebrate Miss Mary’s 70th Birthday,” Rochester Union and Advertiser, March 31, 1897.

“Death Comes to Mary S. Anthony,” Democrat and Chronicle, February 6, 1907.

“Her 70th Birthday: Many Friends Congratulate Miss Mary S. Anthony,” Rochester Union and Advertiser, April 3, 1897.

“Miss Anthony’s Reply to Dr. Crapsey’s Statement from the Pulpit,” Rochester Union and Advertiser, March 24, 1896.